Typological shift in Estonian and Southern Finnic (ESTTYP)

Projekti kirjeldus

Tüpoloogilist nihet saab vaadelda üksiku keele või keelerühma tasandil, uurides üht struktuurilist tunnust, tunnuste rühma või tüüpi või keele grammatilise struktuuri üldpilti (vt nt Hewson 1996; Hintz 2016; Heine & Kuteva 2006). Käesolev projekt läheneb teemale laiemalt: uurime Uurali keelkonna läänepoolse alarühma – lõuna-läänemeresoome (LL) keelte – struktuurilist eristumist. Uuring ühendab areaalse ja intrageneetilise tüpoloogia vaatenurgad ning seob need Euroopa ja Kesk-Balti (KB) piirkonna keelte ning laiemalt Uurali keelkonna kontekstiga.

Läänemeresoome ja saami keeled moodustavad Uurali keelkonna läänepoolseimad rühmad, koos mordva, mari ja permi keeltega vastanduvad nad idapoolsetele mansile, handile ja samojeedi keeltele (vt Saarikivi 2022). Võttes arvesse nii lääne- kui ka ida-uurali keeli, näivad paljude uurali keelte foneetika ja grammatika tüpoloogiliselt sarnased: neil on suhteliselt lihtne silbistruktuur, sõnaalguline rõhk, ees- ja tagavokaalide harmoonia, aglutineeriv morfoloogia, parempoolsed nimisõnafraasid, SOV-sõnajärg jne (vt Comrie 1988; Abondolo & Välijärvi 2023). Siiski paistavad läänemeresoome ja saami keeled silma fusiivsete keelte suunas liikumisega, samas kui teised uurali keeled säilitavad aglutineeriva iseloomu (Laakso 2021).

Lõuna-läänemeresoome keeled (eesti, lõunaeesti, liivi, vadja) on mitmes mõttes ebatüüpilised uurali keeled. Näiteks esinevad neil keerulised fonoloogilised vaheldused, põhiliselt SVO-sõnajärg, uuenduslikud viisid väljendada kaudset evidentsiaalsust ja käske (Metslang 2009; Laakso 2021). Nende fonoloogilistes süsteemides on näiteks kolmeseid kvantiteedivastandusi, toonivastandusi ning spetsiifilisi viise, kuidas sõnaprosoodia ja intonatsioon omavahel suhestuvad (Lehiste jt 2008; Balodis jt 2016; Pajusalu 2012, 2022). Neid unikaalseid nähtusi ei ole veel süsteemselt uuritud. Samuti puuduvad uuringud, mis hõlmaksid märkimisväärset hulka erinevatesse struktuuridomeenidesse (fonoloogia, morfoloogia, süntaks) kuuluvaid tunnuseid ja võtaksid mikroareaalse vaatenurga, mille eesmärk on maksimaalne keelevariantide katvus selles piirkonnas.

Areaalne tüpoloogia täiendab maailmatüpoloogiat, tuvastades mikrovariatsiooni konkreetses piirkonnas (Daniel 2012; Hickey 2017). LL piirkond koos oma lõunapoolsemate variantidega (Kuramaa ja Salatsi liivi, lõunaeesti tartu, mulgi, võro, seto, kraasna, lutsi ja leivu) ning mitte-suguluses kontaktkeeled (balti, slaavi ja (ajaloolised) germaani keeled) moodustavad koos KB keeleala, mida iseloomustavad mitmed ühised jooned fonoloogias, morfoloogias ja süntaksis (Norvik jt 2021; Wiemer jt 2014 soome-ugri, balti ja slaavi keelte ühiste tunnuste kohta). Seda võib käsitleda osana laiemast Läänemere piirkonnast, mille sarnased keelejooned ja uuendused on pälvinud suuremat tähelepanu alates Stolzi (1991) ja Dahli & Koptjevskaja-Tamme (2001a, b) töödest. Ei ole leitud ühtegi Läänemere piirkonda ühendavat keeleliste tunnuste kogumit, mis on viinud aruteluni kontaktide superpositsioonitsooni ja üksteisele mikrotasandil lähenemise üle (Koptjevskaja-Tamm & Wälchli 2001). Sama kehtib ka KB piirkonna kohta (Norvik jt 2021).

See võib peegeldada asjaolu, et läänemeresoome ja saami keeli on erineval määral mõjutanud läänepoolsed mitte-suguluses kontaktkeeled (vt nt Larsson 2001; Tauli 1964; Korhonen 1996 [1980]).

Keelekontakti tulemusena muutuvad keelte struktuurid ja inventarid sarnasemaks. Selle põhjuseks võib olla vormiline sarnasus (nähtuse laenamine), struktuurne sarnasus (mustri laenamine) või nende kombinatsioon (Matras & Sakel 2007; Gardani 2020). Keele erinevate elementide laenatavus on erinev, kuid siiski saab luua laenatavuse skaalad (Thomason & Kaufman 1988; Matras 2009; Gardani 2012). Keele sisemised eeldused määravad, kui tõenäoline on kontaktkeelest uuenduste omaks võtt, ja ennustavad uuenduse positsiooni laenatavuse skaalal (vt nt Thomason & Kaufman 1988). Paljude LL keelte erijoonte võrdlemine indoeuroopa keeltest naaberkeeletega annab väärtuslikku teavet laenatavuse skaalade testimiseks ja keelesiseste muutuse eelduste kindlaks tegemiseks.

Keele arengut mõjutavad ka ühiskondlikud tegurid: standardkeele olemasolu, selle areng ja kasutusvaldkonnad, erinevate keelte kasutus ja staatus ühiskonnas, keele kasutus emakeelena või teise keelena. Selles osas esindavad LL keeled erinevaid olukordi (vt nt Keevallik & Pajusalu 1995; Metslang 2022; Heinsoo & Saar 2015).

Tüpoloogiline nihe võib toimuda ka keelesiseste tegurite tulemusena (Aikhenvald 2006). Näiteks fonoloogilise kvantiteedi (Q) kolmene vaheldus suurendas võimalust väljendada käändevorme fusiivselt ilma käändesufikseid kasutamata, vt eesti Q2 kooli [koːli] ‘kool (omastav)’ ja Q3 kooli [koːːli] ‘kool (osastav)’; selles pikas ja ülipikas kvantiteedivahelduses on oluline ka tonaalne vastandus (Lippus jt 2009, 2011; Asu jt 2016: 141). Balti või Skandinaavia kontaktide mõju tonaalse vastanduse arengule on usutav, kuid selle keeruka prosoodilise vahelduse fonologiseerimiseks peab olema keelesisene sobivus (Pajusalu 2012; Prillop jt 2020).

Üks projekti keskseid ülesandeid on uurida lähemalt väidetavat nihet (enam) fusiivse morfoloogilise tüübi suunas, mida vähemalt osaliselt võib seostada kontaktidega. Eesti keele puhul on ulatuslikke tüpoloogilisi muutusi prosoodias ja käändes traditsiooniliselt seletatud kontaktkeelte, eriti kesk-alamsaksa keele mõjuga (Prillop jt 2020: 30). Fusiivsete joonte kujunemine liivi keeles on seotud läti või vanemate germaani kontaktidega (Grünthal 2015). Keeled erinevad selles, mil määral on neis esindatud erinevaid tüüpe iseloomustavad tunnused; see kehtib ka LL keelte kohta (Viitso 1990, Wälchli 2000, Laakso 2021). Sünonüümia ja redundantsuse suurenemise tulemusena on näha keerukuse suurenemist (Dahl 2004).

LL keelte ja isuri keele tüpoloogilise nihke uurimiseks kasutatakse uusi ulatuslikke andmestikke, nagu Grambank ja UraTyp (https://uralic.clld.org/; vt Norvik jt 2021; Skirgård jt (esitatud) ning andmestike kirjeldus allpool). Näiteks UraTypi andmetel põhinevas uuringus näitas jaotus fonoloogia, morfoloogia ja süntaksi alusel, et lähedased sugulaskeeled võivad sõltuvalt domeenist kuuluda erinevatesse rühmadesse (vt Norvik jt 2022a). Süvitsi minev mikroareaalne uuring on vajalik, et saada parem ülevaade tihedas kontaktis olevate keelte käitumisest. Kvantitatiivsete ja kvalitatiivsete uurimismeetodite kombineeritud kasutamine võimaldab selgitada LL keelte tüpoloogiliselt haruldaste joonte arengut ja olemust ning aidata kaasa keerukate tüpoloogiliste muutuste üldisele mõistmisele.

Käesolev projekt keskendub kolmele LL keelele – eesti, lõunaeesti ja liivi – ning samuti isuri keelele kui põhjapoolsele läänemeresoome (PL) keelele, millel on mitmeid LL keeltega sarnaseid uuenduslikke tüpoloogilisi jooni. Kõik need keeled, välja arvatud eesti keel, on tõsiselt ohustatud, mis teeb nende uurimise kiireloomuliseks. Praegu on Kuramaa liivi keele kõnelejaid teise keelena vaid umbes kakskümmend. Kuramaa liivi keel on aluseks liivi standardkeelele (vt Ernštreits 2012, 2013). Liivi keele teine peamine variant, Salatsi liivi, hääbus 19. sajandil, kuid hiljuti on avaldatud selle põhiandmed ja grammatika ülevaade (Winkler & Pajusalu 2016, 2018). Liivi keele sotsiolingvistilist olukorda ja struktuuri on viimase kümnendi jooksul põhjalikult uuritud (nt Pajusalu 2014; Norvik 2015; Kallio 2016; Kiparsky 2017; O’Rourke 2018), kuid liivi keele võrdlevaid analüüse on vähe (vrd Wälchli 2000; Grünthal 2003, 2015).

Siinses projektis pööratakse erilist tähelepanu ka lõunaeesti keelesaartele: Leivu ja Lutsi Lätis ning Kraasna Venemaal (vt Balodis & Pajusalu 2021; Weber 2021). Kraasna keel oli kasutuses kuni 20. sajandi esimeste kümnenditeni. Leivu ja lutsi keele viimased emakeelsed kõnelejad surid suhteliselt hiljuti, aga kohalikud kogukonnad on aktiivsed, et säilitada oma pärimuskultuuri (Balodis 2021). Lõunaeesti keel oli esimene, mis eraldus algläänemeresoome keelest (Sammallahti 1977; Kallio 2014; Prillop jt 2020). Liivi keel eraldus järgmisena pärast lõunaeesti keelt (Viitso 1985). Leivu keel oli esimene, mis eraldus lõunaeesti keeleühtsusest (Kallio 2021). Leivu keelel on ka vanad kontaktid liivi keelega (Viitso 2009). Seetõttu on leivu ja lutsi keel tähtsad LL keeleala kujunemise mõistmiseks nii ajaloolisest kui ka tüpoloogilisest vaatenurgast (vt Norvik jt 2021).

Isuri keel on üks nooremaid PL keeli (Kallio 2007: 243; Pajusalu 2014; Prillop jt 2020) ning geograafiliselt lähim PL keel lõunaeesti keelele. Huvitaval kombel jagavad isuri ja LL keeled, sh lõunaeesti keel, teatud (morfo)fonoloogilisi ja morfosüntaktilisi uuendusi ning omapäraseid tüpoloogilisi jooni (vt nt Markus jt 2013; Saar 2017, 2019). Kuna isuri keel on üks vähim uuritud läänemeresoome keeli, vajab selle seos keelkonna teiste keeltega põhjalikumat analüüsi.

Erinevate keelevaldkondade ja nende võimalike omavaheliste seoste ühisuuring on tüpoloogilistes uuringutes saanud suhteliselt vähe tähelepanu (vt nt Plank 1998; Luraghi 2017; Klumpp jt 2018; Miestamo 2018). Uute ulatuslike andmebaaside nagu Grambank ja UraTyp loomine avab uusi võimalusi, sealhulgas piirkonnaspetsiifilistele uuringutele. Siinne projekt võimaldab heita rohkem valgust LL piirkonnale, kuna seni ei ole selle piirkonna keeli süstemaatiliselt uuritud viisil, nagu me siin plaanime teha.

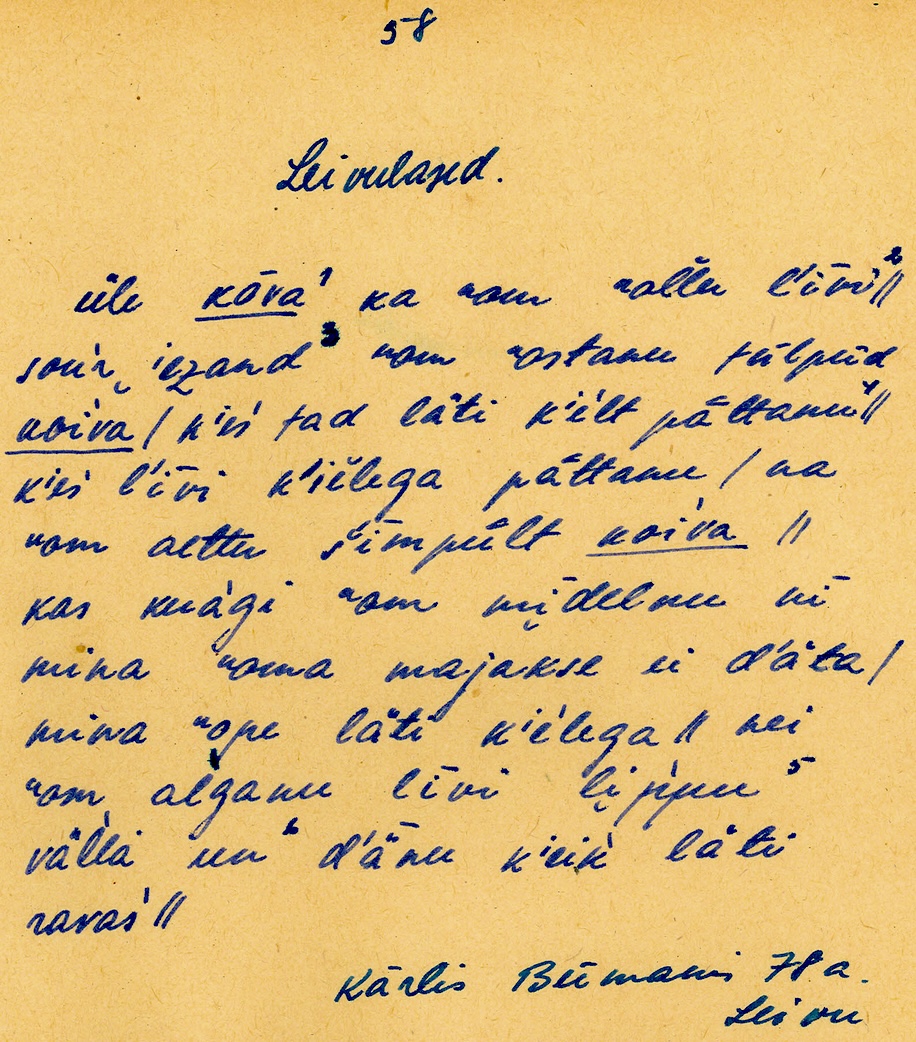

Päisepilt: Leivu keele välitööde märkmed, mille kirjutas üles Heli Tõugjas Kārlis Būmaniselt Ilzenes Lätis 1956. (Allikas: Tartu Ülikooli eesti murrete ja sugulaskeelte arhiiv, arhiivinumber T0258)