Typological shift in Estonian and Southern Finnic (ESTTYP)

Uuritavad keeled

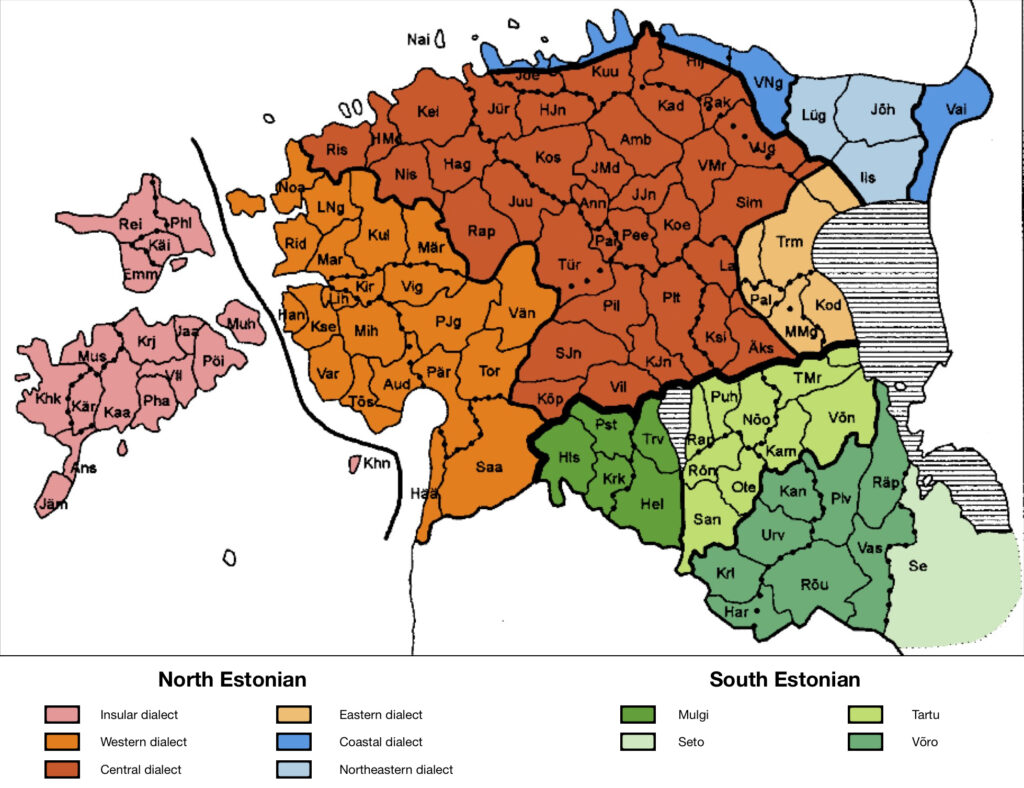

See kaart on muudetud versioon kahest kaardist, mille lõid Timo Rantanen jt „Uurali keelte atlase“ osana: kaart 1, kaart 2.

Muudatused tegi Uldis Balodis selle veebisaidi loomise käigus.

(1) Eesti keele ala

See kaart on muudetud versioon kaardist, mis ilmus teoses „Eesti murded ja kohanimed“ (3. trükk 2018).

Muudatused tegi Uldis Balodis selle veebisaidi loomise käigus.

a. Eesti kirjakeel

Eesti keel (ISO 639-3: est, ekk, Glottocode: esto1258) on Eesti Vabariigi ametlik keel ja üks Euroopa Liidu ametlikest keeltest. 2022. aasta seisuga rääkis eesti keelt ligikaudu 1,2 miljonit inimest üle maailma. Esimesed kirjalikud eesti keele näited pärinevad 16. sajandist. Eesti keele standardiseerimisega alustati 19. sajandil ning tänapäeva standardkeel põhineb põhjaeesti keelel. Ajaloo jooksul on eesti keel olnud tihedas kontaktis balti, germaani ja slaavi keeltega, mis kajastub sõnavaras ja morfosüntaksis. Eesti keel on tuntud kolme välte poolest (lühike, pikk ja ülipikk), mis avaldub silpide kestussuhetes.

Foto: Eesti lipud jaanipäeval. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Kuressaare, Eesti, 2014.

b. Põhjaeesti keel

Saarte murre

Saarte murret (Glottocode: sart1250) räägitakse Lääne-Eesti saartel alates Kihnust lõunas kuni Hiiumaani põhjas. Seda piirkonda ja naaber-rannikualasid asustasid ajalooliselt ka rootsi keele kõnelejad ning seetõttu on saarte murre saanud mitmeid rootsi keele mõjutusi, sealhulgas rootsipärane laulev intonatsioon ja laensõnad eestirootsi keelest, nt sõnad trasu ~ träsu ‘räbal’, krenkima ~ kränkima ‘haige olema’ on kasutusel Hiiumaal. Kihnu saare keel on saarte murrakutest kõige erinevam ja sisaldab häälikumuutusi, mida mujal eesti keeles ei esine, vrd nt Kihnu jõrm, njapp ja kirjakeelne hirm, näpp. Kihnu murrak on ka ainus põhjaeesti variant, millel on õ-harmoonia, vrd nt Kihnu olõ, tugõv ja kirjakeelne ole, tugev.

Foto: Kihnu naised Kihnu Muuseumis kihnu keele töörühma kohtumisel. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Linaküla, Kihnu saar, Eesti, 2014.

Läänemurre

Läänemurret (Glottocode: laan1234) räägitakse Lääne- ja Edela-Eesti mandriosas Lääne- ja Pärnumaal. Üleminek lääne- ja keskmurde vahel on järkjärguline ning teatud läänemurdejooni leidub ka keskmurde alal. Lääne ja saarte murretes on rõhuta silpide reduktsioon suurem kui keskmurdes, nt läänemurde saarlest ja kirjakeelne saarlased. Läänemurret iseloomustab ka v asendamine b-ga kahe vokaali vahel, nt läänemurde kõba kibi vs. kirjakeelne kõva kivi, v kadumine enne labiaalvokaale u, ü, ö, nt läänemurde sui vs. kirjakeelne suvi, ja sõnaalguliste konsonantühendite lihtsustumine, nt läänemurde leit vs. kirjakeelne kleit. Rannikualad (Noarootsi, Vormsi), kus ajalooliselt elasid rootsi keele kõnelejad, näitavad samuti rootsi mõju, samas kui lõunapoolsed alad (Häädemeeste, Saarde) näitavad nii mulgi kui ka liivi mõju.

Foto: Rannikuvaade. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Tahkuranna, Eesti, 2023.

Keskmurre

Keskmurre (Glottocode: kesk1234) katab ulatusliku ala: ligikaudu kolmandiku Eesti territooriumist, kuid on vähem ühtne kui teised eesti murded ning moodustab pigem suure üleminekutsooni nende vahel, jagades jooni eesti kirjakeelega. Näiteks kattub keskmurde sõnavara suurel määral kirjakeele põhisõnavaraga. Keskmurret iseloomustavad tunnused on näiteks pikkade vokaalide diftongistumine, nt keskmurde põesas, nüid vs. kirjakeelne põõsas, nüüd, mitmuse moodustamine üldistunud de-vormiga, nt keskmurde jalgadel, külades vs. jalul, külis.

Foto: Talumaja Kesk-Eesti maapiirkonnas. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, 2019.

Idamurre

Idamurret (Glottocode: idae1234) räägitakse Peipsi järve lääne- ja looderannikul Ida-Eestis. Idamurre sarnaneb kirdemurde ja vadja keelega, nt on levinud vokaal õ ja st asemel kasutatakse ss-i, nt ida issun, mussad, vedess vs. kirjakeelne istun, mustad, veest. Idamurre sarnaneb ka lõunaeesti vormidega, nt n– eesütlev, nt ida ilman vs. kirjakeelne ilmas, samuti sarnaneb seto ja kirde murdega translatiivi märkimisel st-ga, nt ida suurest mehest vs. kirjakeelne suureks meheks. Idamurre on läänemeresoome keelte seas tähelepanuväärne ka oma unikaalsete eitusverbivormide poolest: idamurde esin õle, esid õle, es õle, esimä olõ, esittä õle, esid õle vs. kirjakeelne ma ei olnud, sa ei olnud, ta ei olnud, me ei olnud, te ei olnud, nad ei olnud. Idamurret tuntakse ka arhailise Kodavere murraku ulatusliku dokumenteerimise poolest, mida tegi keeleteadlane Lauri Kettunen 1910. aastatel.

Foto: Kallaste külatänav Peipsi järve ääres. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Kallaste, Eesti, 2022.

Rannamurre

Rannamurret räägitakse Eesti põhjaranniku äärmises osas, alates alast vahetult Tallinnast läänes kuni Ida-Virumaa läänepiirini ja seejärel mööda kitsast riba kirdemurde ja Eesti-Vene piiri vahel Ida-Virumaal. Rannamurdes puudub täishäälik õ ning teise ja kolmanda välte vahel ei tehta seal vahet. Rannamurre sarnaneb sõnavara poolest soome keelega. Veel üks tähelepanuväärne tunnus on see, et rannamurdes on tegusõna ainsuse kolmanda isiku oleviku vormid markeerimata, nt rannamurde näke, viska vs. kirjakeelne näeb, viskab. Tingiv kõneviis võib olla märgitud sufiksitega -isi või –ksi, nt rannamurde veisin, veiksin vs. kirjakeelne ma võiksin.

Foto: Vaade Nigula talule Natturi külas. Allikas: Lembit Odres, 1972 ERM Fk 3068:1873

Kirdemurre

Kirdemurret räägitakse Peipsi järve põhjarannikust kuni Eesti põhjarannikuni Ida-Virumaal. Täishäälik õ on kirdemurdes sagedasem kui kirjakeeles, nt kirde õli, kõht, õtse vs. kirjakeelne oli, koht, otse. Kirdemurre sarnaneb sõnavara poolest vadja keelega. Vadja keele ala asub vahetult kirdemurde ala idaservas ja ajalooliselt elas selles Eesti osas ka vadja kogukondi, nt segakeelne eesti-vadja-vene kogukond Iisaku lähedal, tuntud kui poluvernikud ‘poolusklikud’, kes ühendasid õigeusu ja luteri traditsioone. Tegusõnade ainsuse kolmanda isiku oleviku vormid on markeeritud sufiksiga -b nagu kirjakeeles, kuid tingiva kõneviisi vormid on kirdemurdes märgitud sufiksitega –s(i) või -(i)ses(i), nt kirde tegesin, tegesesin vs. kirjakeelne ma teeks.

Foto: Vaade Pirda talule Jõuga külas Iisaku kihelkonnas. Allikas: Uudo Rips, ERM Fk 1203:20

c. Lõunaeesti keel

Mulgi

Mulgi (Glottokood: mulg1249) on läänepoolseim lõunaeesti keelekuju ja seda räägitakse Võrtsjärvest läänes ja kuni Läti piirini lõunas. Ajalooliselt räägiti mulgi keelt ka Lätis Põhja-Vidzeme piirkonnas. 2011. aasta rahvaloenduse andmetel rääkis mulgi keelt 9698 inimest. Kirjalikest lõunaeesti variantidest on mulgi kirjakeel kõige hiljem välja arenenud. Praegu koostatakse mulgi keele sõnaraamatut ja mulgikeelne ajaleht Üitsainus Mulgimaa ilmub kord kuus. Mulgi Kultuuri Instituut korraldab mulgi keele ja kultuuriga seotud tööd ja üritusi. Mulgi on lõunaeesti keelekujudest kõige sarnasem põhjaeesti keelele – eriti läänemurdele, millega see piirneb. Ida-Mulgi murrakuid iseloomustab suurem sarnasus Tartu lõunaeesti variandiga ja neis on rohkem tüüpilisi lõunaeesti jooni. Mulgi keelele on iseloomulik a ja ä muutumine e-ks alates kolmandast silbist, nt mulgi armasteme vs. kirjakeelne armastama. Läti ja liivi keele kontaktide tõttu on mulgi keeles ka ühiseid sõnu mõlemaga, nt mulgi puuts, toŕt ja läti pūce ‘kakk’, stārķis ‘toonekurg’, mulgi kurtma, uisk vs. Salatsi liivi kurt ~ kūrt ‘seisma’, ūšk ‘uss’.

Foto: Mulgi sõnaraamatu töörühm (vasakult: Alli Laande, Marili Tomingas, Kristi Ilves, Karl Pajusalu). Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Mustla, Eesti, 2022.

Seto

Seto (Glottokood: seto1244) on idapoolseim lõunaeesti keelekuju ja seda räägitakse piirkonnas, mis ulatub üle praeguse Eesti-Vene piiri. See jaotus tekkis selle territooriumi annekteerimise tulemusena Nõukogude okupatsiooni ajal. Seto keele rääkijaid elab mõlemal pool piiri. 2011. aasta rahvaloenduse andmetel rääkis seto keelt 12 549 inimest. Seto keeles on aastakümneid eksisteerinud elav kirjandustraditsioon, mille raames ilmub regulaarselt mitmesuguseid väljaandeid. Seto keele ja kultuuri alast tööd koordineerib Seto Instituut ning setokeelne ajaleht Setomaa ilmub kord kuus. Lisaks ä, ü, õ vokaalharmooniale esineb mõnes seto variandis ka piiratud ö-harmooniat, nt jänö ‘jänku’. Seto keelele on ainulaadne h esinemine kõigis positsioonides, sealhulgas seesütlevas käändes ja sõna lõpus, nt hõbõhhõh ‘hõbedas’, imeh ‘ime’. Sõnalõpuline kõrisulghäälik täidab olulisi grammatilisi funktsioone, tähistades teise isiku ainsuse käskivat kõneviisi ja nimetava mitmuse vormi, nt annaq ‘anna!’, tarõq ‘toad’. Enamik konsonante võib olla palataliseeritud. Seto keeles on ka palju vene laensõnu, nt seto paaba, tsuuda vs. vene баба (bába) ‘vana naine’, чудо (tšúdo) ‘ime’. Seto ja võru keel on lõunaeesti keele sees tihedalt seotud, kuid neid eristavad eelkõige sõnavara ja hääldus. Kultuuriliselt eristuvad traditsiooniliselt luteriusulised võru keele rääkijad ja õigeusklikud seto keele rääkijad ka usulise kuuluvuse poolest. Kraasna ja Lutsi keelesaare variandid on seto keelega eriti tihedalt seotud.

Foto: Seto tsäi- ehk teemaja, mille nimi on kirjutatud seto keeles. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Värska, Setomaa, Eesti, 2019.

Tartu

Tartu (Glottokood: tart1244) on lõunaeesti keelekuju, mis on levinud lõunaeesti keeleala põhjaosas, Võrtsjärve ja Peipsi järve vahel, võru keelealast põhja pool. 2011. aasta rahvaloenduse andmetel rääkis tartu keelt 4109 inimest. Lõunaeesti kirjakeele vorm – nn tartu keel – kujunes 17.–19. sajandil ja põhines lõunaeesti tartu ja võru keelevariandil. Tartu keel on kõige sarnasem mulgi keelele. Erinevused ilmnevad näiteks illatiivivormide moodustamises – tartu illatiivi tunnus on -de, samas kui mulgi kasutab -s(se), nt tartu kambrede, mulgi kamres ‘tubadesse’. Tartu keelele on iseloomulik ka isikulõppude kasutamine mineviku kesksõna ja eituse vormides, nt olluva ‘nad on olnud’, nännümi ‘me oleme näinud’, ei annava ‘nad ei anna’. Tartu murrakuid, mis piirnevad põhjaeesti keelega põhjas, mulgi keelega läänes ja võro keelega lõunas, iseloomustavad täiendavad sarnasused nende variantidega.

Foto: Püha Maarja luteri kirik Otepää lähedal. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Otepää, Eesti, 2019.

Võro

Võro (ISO 639-3: vro, Glottocode: voro1243) on lõunaeesti keelekuju, mis on kasutusel Kagu-Eestis Peipsi järvest kuni Läti piirini, Tartu keelealast lõuna pool ja Setomaast lääne pool. Võro keelt räägitakse piiratud määral ka naaberpiirkondades Lätis, nt Vana-Laitsna (läti Veclaicene). Võro on kõige laialdasemalt räägitav lõunaeesti keele variant. 2011. aasta rahvaloenduse andmetel rääkis võro keelt 74 499 inimest. Võro keele ja kultuuri alast tööd koordineerib Võro Instituut ning kaks korda kuus ilmub võrokeelne ajaleht Uma Leht. Nagu eespool Seto kirjelduse juures öeldud, on võro ja seto lõunaeesti keele sees eriti tihedalt seotud ning neid on mõnikord kirjeldatud kui ühe lõunaeesti murde kahte allvarianti. Siiski on nende vahel erinevusi. Näiteks on seto keelt mõjutanud vene keel h– ja l-häälikute häälduses. Paljudel levinud sõnadel on erinev hääldus, nt võro hää, seto hüä ‘hea’, võro häste, seto höste ‘hästi’, võro egä, seto õga ‘iga’. Morfoloogilised erinevused hõlmavad erinevaid translatiivseid lõppe: võro kasutab –ss, seto aga –st. Mõlemat tüüpi vorme leidub Lutsi keelesaare variandis.

Foto: Kaks meest ootamas bussipeatuses. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Orava, Võrumaa, Eesti, 2019.

(2) Läänemeresoome keeled ja variandid Lätis

a. Lõunaeesti keelesaared

Leivu

Leivu (Glottokood: leiv1235) on varaseim lõunaeesti keelekuju ja leivu keel eraldus ajaloolisest lõunaeesti keelest. Seetõttu on leivu kaugem sugulane lutsi, kraasna, võro ja seto keelega kui need omavahel. Leivu võib olla järeltulija dokumenteerimata Atzele maa keelele, mis asus tänapäeva Kirde-Lätis. Viimane teadaolev leivu emakeelne kõneleja oli pärit Pajušilla (Kārklupe) külast ja suri 1988. aastal. Nagu teisedki lõunapoolsed läänemeresoome keeled, millel ei ole enam emakeelseid kõnelejaid, on ka leivu järeltulijad teadlikud oma pärandist. Projekti põhitäitja Pire Teras on kirjeldanud leivu häälikusüsteemi ja selle ainulaadseid prosoodilisi jooni. Leivus on palju läti keele laene, nt bikšikseq ‘püksid (deminutiiv)’, zenʹtʹ, brougan, laimig, daužʹma, vrd läti bikses ‘püksid’, zēns, zeņķis ‘poiss’, brūtgāns ‘peigmees’, laimīgs ‘õnnelik’, dauzīt ‘peksma’. Lisaks läti laenudele iseloomustab leivu keelt katketooni ehk stød’i kujunema hakkamine. See tunnus on iseloomulik läti keelele ja esineb toonivastandusena liivi keeles, samas kui lutsi ja tõenäoliselt ka kreevini vadja keeles esineb see vaid hääldusvariandina. Leivu rahvast ja kogukondi kirjeldatakse täpsemalt siin.

Foto: Eesti keeleteadlane Paul Ariste (keskel) koos Leivu kõnelejate Alfred Petersoni (vasakul) ja Alide Petersoniga (paremal). Allikas: Valter Niilus, 1935, Paikna (Paiķēni), Läti, ERM Fk 724: 3

Lutsi

Lutsi (Glottokood: luts1235) on lõunaeesti keelekuju, mida on räägitud mitmeid sajandeid, olles enamasti teistest lõunaeesti keele kõnelejatest Eestis eraldatud. Lutsit iseloomustab pikaajaline ja intensiivne kontakt läti ja latgali keelega ning samuti vene, poola, valgevene ja jidiši keelega. 19. sajandi lõpus räägiti lutsi keelt mitmekümnes külas Ludza linna põhja-, ida- ja lõunaosas (ajaloolistes Mērdzene (Mihalova), Pilda, Nirza ja Briģi (Janovole) kihelkonnas). Viimased kõnelejad elasid Jāni küläs (Lielie Tjapši) ja Kirbu küläs (Škirpāni) Ludza lõunaosas. Viimane emakeelne kõneleja elas kuni 1983. aastani, viimane vestlusoskusega kõneleja suri 2006. aastal, viimane osaline kõneleja suri 2014. aastal. 2020. aastatel on alles mitu lutside ja lutsi keele mäletajat. Lutsi järeltulijad on teadlikud oma pärandist ja suhtuvad sellesse positiivselt. Keele elustamise algatused on juba käimas. Projekti põhitäitja Uldis Balodis on avaldanud lutsi keele ja kultuuri õpiku. Lutsis nagu teisteski Lätis räägitavates läänemeresoome keeltes esineb katketoon ehk stød, kuid ainult teatud vokaalidevaheliste konsonantide hääldusvariandina. Lutsis esinevad nii setole kui ka võrole iseloomulikud vormid. Seega esinevad lutsis seto-laadsed vormid hüä, höste, õga, aga ka võro-laadne egä. Samuti on lutsis nii h-inessiiv (nagu setos ja võros) kui ka n-inessiiv (nagu võro läänepoolsetes murrakutes) ning st-translatiiv (nagu setos) ja s-translatiiv (nagu võros). Lutsi rahvast ja kogukondi kirjeldatakse täpsemalt siin.

Foto: Lutsi järeltulijad koos projekti teaduri Uldis Balodisega lutsi keele ja kultuuri õpiku esitlusel. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Ludza, Läti, 2020.

b. Liivi keel

Kuramaa liivi

Kuramaa liivlased (ISO 639-3: liv, Glottocode: west1760) elasid ajalooliselt kalurikülade ahelikus Kuramaa (läti Kurzeme) põhjarannikul Lätis piirkonnas, mida tuntakse kui Līvõd rānda (Liivi rand). 1950. aastatel sunniti Kuramaa liivlased oma kodurannikult lahkuma Nõukogude okupatsioonirežiimi militariseerimise tõttu. Tänapäeval elab enamik liivlasi Riias, Ventspilsis ja Kolkas. 2020. aastatel on umbes 20 vestlusoskusega (peamiselt L2) kõnelejat ja umbes 200 inimest, kellel on liivi keelest algteadmised. Mõned L2 kõnelejad on keeleteadlased ega ole liivlaste järeltulijad. Kuramaa liivi keel on ainus Lätis räägitav läänemeresoome keel, mida on õpetatud koolides. Läti sõdadevahelise iseseisvuse ajal anti liivi keele tunde rannakülade koolides. Sel ajal avaldati ka raamatuid ja regulaarselt ilmus ajaleht Līvli. Praegu on käimas keele elustamise tegevused, mida juhib Läti Ülikooli Liivi Instituut, mis koordineerib ja toetab tööd kõigis liivi keele ja kultuuriga seotud valdkondades. Tartu Ülikool on toetanud liivi keele uurimist ja pakkunud keelekursusi üle sajandi. 2023. aastal avaldati esimene eestikeelne liivi keele õpik.

Foto: Liivi laste ja noorte suvekooli „Mierlinkizt“ osalejad iga-aastastel Liivi pidustustel, kus austatakse Mierjemā (Mereema). Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Irē (Mazirbe), Läti, 2023.

Salatsi liivi

Salatsi liivlased (ISO 639-3: liv, Glottocode: east2326) on Vidzeme (Metsepole) liivlaste järeltulijad, kes elasid Lääne-Vidzemes ja väikeses Eesti rannikupiirkonnas Häädemeeste lõunaosas. Tänapäeva järeltulijad on teadlikud oma pärandist ja suhtuvad sellesse positiivselt. Salatsi liivi keel on ainus dokumenteeritud Vidzeme liivi keele variant ja seda räägiti ajalooliselt Svētciemsi lähedal Salacgrīvast lõuna pool Lätis. Viimased teadaolevad kõnelejad elasid 1860. aastatel, kuid Salatsi liivi keele mäletajaid dokumenteeriti veel 20. sajandi alguses. Projekti vastutav täitja Karl Pajusalu on hiljuti avaldanud „Salatsi liivi keele teejuhi“ (2023) koostöös Eberhard Winkleriga eesti ja läti keeles ning mitmeid Salatsi liivi luulekogusid (autorina Ķempi Kārl). Läti Ülikooli Liivi Instituut, Tartu Ülikool ja Göttingeni Ülikool tegelevad Salatsi liivi keele uurimisega.

Foto: Vidzeme liivlaste järeltulijad – Lielnorsi perekonna liikmed – uurivad oma sugupuud. Allikas: Rasma Noriņa, Riia, Läti, 2012.

(3) Lõuna-läänemeresoome keeled Venemaal

a. Vadja keel

Vadja (ISO 639-3: vot, Glottocode: voti1245) kodumaa on Ingerimaal ning vadja ja isuri keele kõnelejate külad on ajalooliselt asunud lähestikku või kõrvuti. See piirkond asub Kingissepa rajoonis Leningradi oblastis Venemaa Föderatsioonis, tänapäeva Eesti piiri lähedal. Ajalooliselt elasid vadjalased ka teistes piirkondades, millest mõned ulatusid Kirde- ja Ida-Eestisse. Kreevini keel (ISO 639-3: zkv, Glottocode: krev1234) – vadja keele variant – oli kasutusel kuni 19. sajandini Lõuna-Kesk-Lätis Bauska lähedal. Praegu elavad vadja keele kõnelejad endiselt Lauga jõe (vene keeles: Luga) suudme lähedal Jõgõperä (Krakolje), Liivtšülä (Peski) ja Luutsa/Luuditsa (Luzhitsõ) külas. 2010. aasta rahvaloenduse andmetel elas Venemaa Föderatsioonis 64 vadjalast. Samuti oli 2010. aastal teada 68 vadja keele kõnelejat. Vadja keele dokumenteerimine jätkub ning viimastel aastatel on vadja keele uurija Heinike Heinsoo avaldanud mitmeid keeleõppeks mõeldud raamatuid (nt õpik, lugemik, vestmik).

Foto: Vadja keele uurija Heinike Heinsoo (vasakul) koos projekti põhitäitja Eva Saarega (paremal) välitöödel isuri ja vadja külades. Allikas: UT AEDKL, DF0041-002; Monastõrki, Venemaa, 2015.

b. Isuri keel

Isurid (ISO 639-3: izh, Glottocode: ingr1248) on ajalooliselt elanud mitmes külas Lauga (vene keeles: Luga) ja Hevaha (Kovaši) jõe ääres ning Soikkola (Soikino) ja Kurgola (Kurgolovo) poolsaarel. Need piirkonnad asuvad Kingissepa ja Lomonossovi rajoonis Leningradi oblastis Venemaa Föderatsioonis. 2010. aasta rahvaloenduse andmetel elas Venemaa Föderatsioonis 266 isurit. Samuti oli 2010. aastal teada 123 isuri keele kõnelejat. Erinevalt teistest selle projekti keeltest on isuri põhja-läänemeresoome keel, kuid jagab lõuna-läänemeresoome keeltega teatud (morfo)fonoloogilisi ja morfosüntaktilisi uuendusi ning omapäraseid tüpoloogilisi jooni.

Foto: ERMi uurija R. Piiri intervjueerib Natalja Nikiforovat (Ilja Konstantinovi abikaasa), sündinud 1909 (isurid). Allikas: Aado Lintrop, 1979, ERM Fk 1979:60. ERM Fk 1979:60

c. Lõunaeesti keelevariandid

Idaseto

Idaseto (Glottocode: east2808) on lõunaeesti keelekuju, mis on kasutusel Petseris (Pechory) ja teistes Seto külades, mis asuvad tänapäeva Eesti-Vene piirist ida pool. Idasetot on tugevalt mõjutanud kontakt vene keelega, samas kui kontakt läänepoolsete seto variantide või eesti kirjakeelega on olnud vähene. Kuigi vene laensõnu leidub ka teistes seto variantides, on mõned neist idasetos sagedasemad, nt joosś, koomot, räbinäs, tsäädsä, plaavatama, vrd ёж (jož) ‘siil’, комната (kómnata) ‘tuba’, рябина (rjabína) ‘pihlakas’, дядя (djádja) ‘onu’, плавать (plávat) ‘ujuma’.

Foto: Maantee Seto küla Mitkovitsy lähedal. Allikas: Uldis Balodis, Mitkovitsy ja Podles’e, Setomaa, 2019.

Kraasna

Ainus kolmest lõunaeesti keelesaare keelest (kraasna, leivu, lutsi), mida ajalooliselt ei räägitud Lätis. Kraasna keelt (Glottocode: kraa1234) dokumenteerisid 20. sajandi alguses eesti uurija Oskar Kallas ja soome uurija Heikki Ojansuu. Seda räägiti külade võrgustikus Krasnogorodski linna lähedal Venemaal, tänapäeva Läti piiri lähedal ja vaid mõnekümne kilomeetri kaugusel lutsi põhjapoolseimatest küladest. Kraasna oli esimene lõunaeesti keelesaarevariant, mille igapäevane kasutus lakkas – tõenäoliselt juba enne teist maailmasõda. 1952. ja 1966. aastal leidis eesti uurija Paulopriit Voolaine veel mõned inimesed, kellel oli fragmentaarne teadmine kraasna keelest, ning 2004. aastal leidis Tartu Ülikooli ekspeditsioon Ivatsova külas kaks perekonda, kes olid endiselt teadlikud oma eesti päritolust. Kraasna rahvast ja nende kogukondi kirjeldatakse täpsemalt siin.

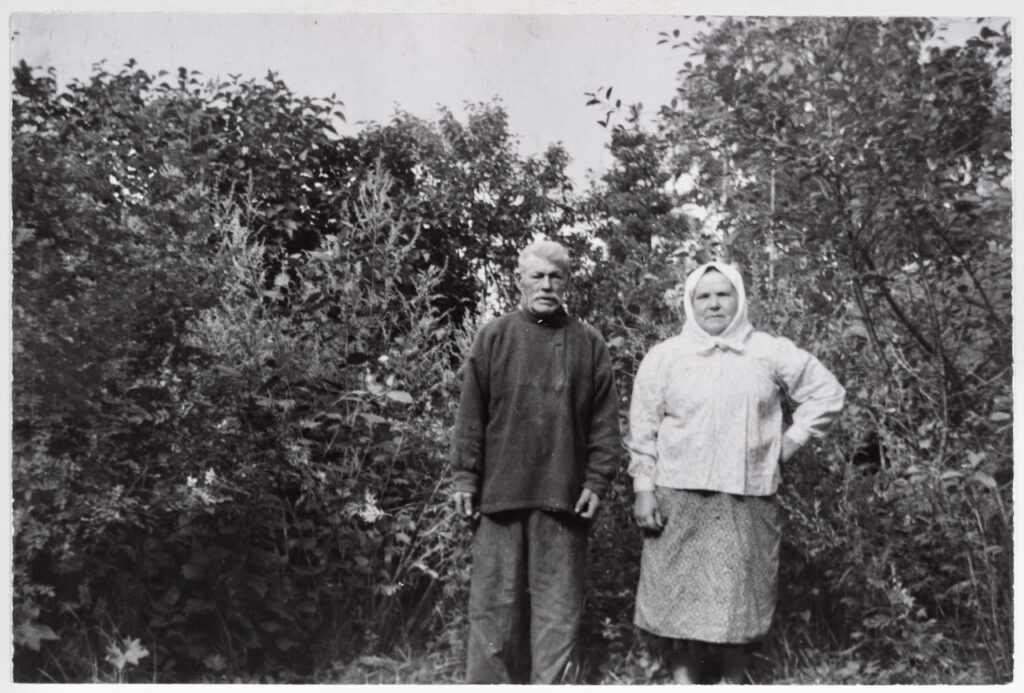

Foto: Kraasna keele mäletaja Jegor Vassiljev koos oma abikaasaga. Allikas: Paulopriit Voolaine, 1966, Mõisa (Myza), Venemaa, ERM Fk 1508: 138

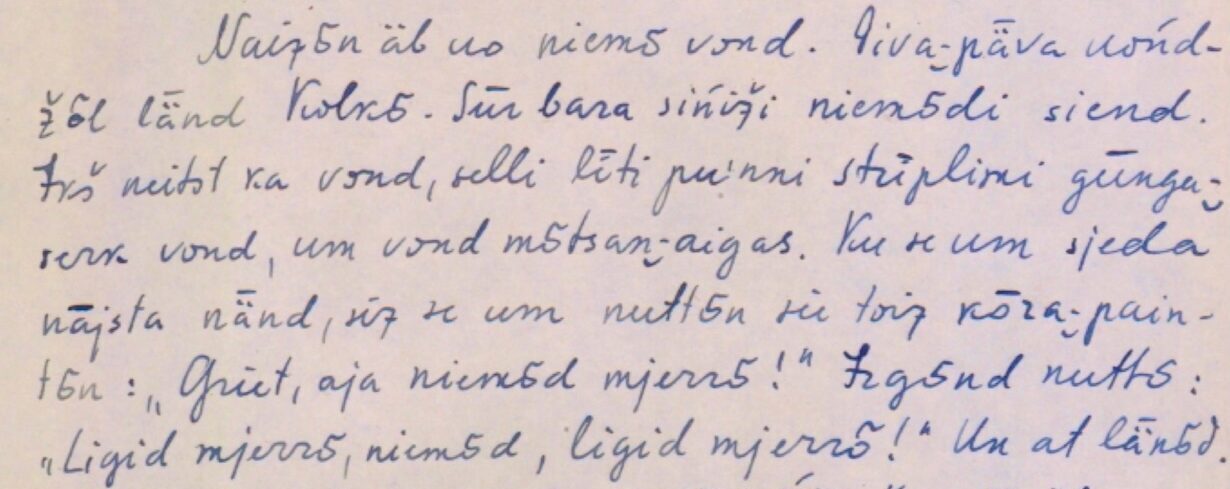

Päisepilt: Liivi keele välitööde üleskirjutused, mille tegi Oskar Loorits Didrik Brenkoult Sīkrõgis (Sīkrags) Lätis 1922. Allikas: Tartu Ülikooli eesti murrete ja sugulaskeelte arhiiv, arhiivinumber LFS0244.